It takes a big heart – and a lot of guts – to fight for social justice in a new country. But Korean Ph.D. student Ahyoung Song is just the woman for the job.

Story by: Lydia Siriprakorn

Ahyoung Song wouldn’t call herself a superhero, but to the many runaway Korean teenagers and homeless LA women she’s worked with, she is as close as it gets.

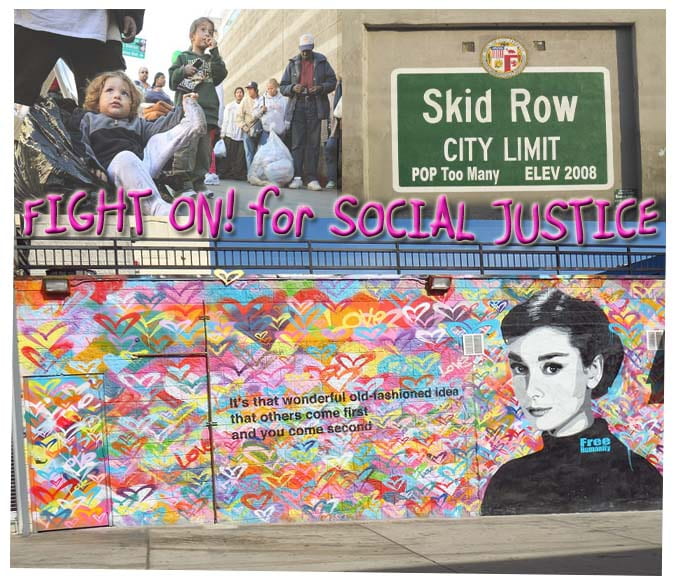

Song is a Ph.D. student in the School of Social Work from South Korea. She’s also a wife and mother of two – balancing all of those roles with her lifelong fight for social justice. Last year, she received the B.B. Robbie Rossman Annual Memorial Child Maltreatment Research Award for her presentation on domestic violence. This year, she continues on the fast track to graduation and brings her passion to some of the roughest neighborhoods in Los Angeles.

Q. Was there a moment when you witnessed social injustice that made a lasting impression on you?

Ahyoung: When I was an undergraduate student, I was a member of a student group for social change in our community in Korea. I volunteered at community centers. Most of them served poor kids and kids who ran away from home and didn’t go to school. I helped them prepare for their degree or graduation exam. Sometimes I was their counselor because they showed behavioral problems and anger. Even though some of them were only 12 or 13 years old, many were engaged in crime. I knew I needed to find some way to deliver my ideas and passions to change these social issues. I decided to pursue a higher education in the U.S. because in Korea, there is more of a tendency for people to listen and follow authorities.

Q. What are you working on right now?

Ahyoung: Currently I’m working on a very interesting project. We’re collaborating with agencies and shelters to develop effective HIV prevention interventions to reduce unprotected sex for homeless women. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention of Los Angeles’ website lists very effective ways to prevent unprotected sex, selected based on very rigorous testing. But those interventions were tested on women or other populations, not homeless women.

Homeless women, compared to other women, are in a complicated situation. Sometimes they have sex for need – food or shelter – and put themselves in danger. I wanted to find what the barriers are for homeless women to use condoms within these dangerous situations. We’re now in the stage of implementing these interventions in the community and collecting data to evaluate if they work with homeless women in this particular area or not.

Q. Do you have a big dream you hope to accomplish?

Ahyoung: Ultimately I really want to go back to Korea because the homeless population and HIV prevalence rate are increasing but there are few resources available. Talking about condoms or sex in public is something people don’t really do there. So I believe that my experiences at USC will help me implement programs to help these populations.

I really want to build up the community effort and build a residence for homeless women and children. But first, I have to work hard to change people’s minds. The public distances themselves from homeless people in Korea, which makes it hard to fundraise to help the homeless. There’s a stigma that they are lazy or irresponsible. But really, who wants to stay on the street?

Lydia Siriprakorn is pursuing a Master of Professional Writing degree and is from Washington, D.C.